Tips and Resources

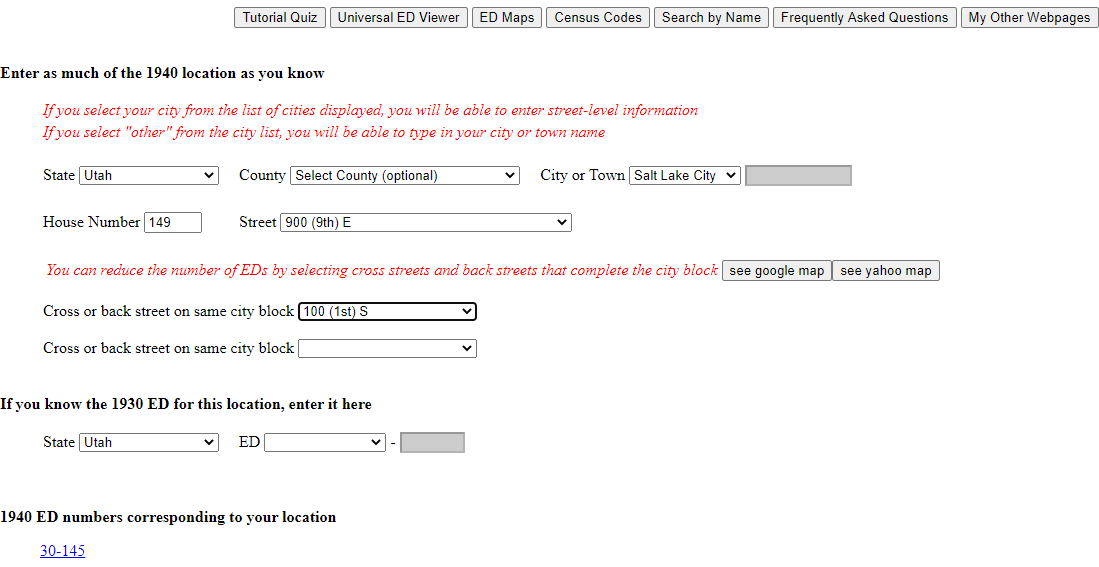

If you think you know where someone is living in a census year based on earlier or later censuses, city directories or other records, yet you can’t find them through searches, Steve Morse’s One-Step tool can help you avoid a lot of manual searching. The tool provides you the enumeration district based on either a street address or an enumeration district from another census year, so you have a smaller set to peruse.

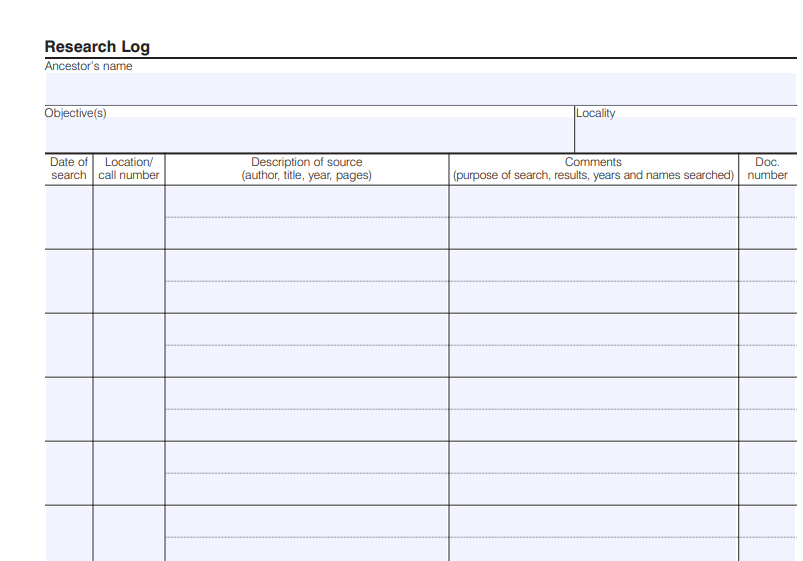

It’s easy to get excited following clues from one record to another and to forget to record what and where we have searched. However, keeping a research log will pay off in the long run by helping to avoid repeating work we have already done, and identifying record sets we may have missed. The research log should include the date, repository or website, record/record set or database searched, the search parameters (names, date ranges, locations, keywords etc.), and findings or lack thereof. You can easily create your own research log in word processing or spreadsheet software, or download templates from Familysearch as in the example below or other sites.

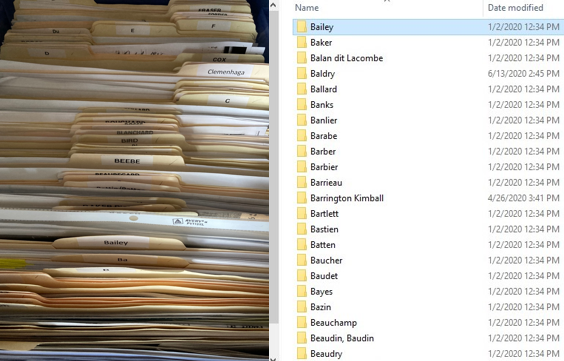

Like most of us who have been doing genealogy for a while, initially all my records were paper. As digital resources increased, I found I had a mixture of paper and digital records and didn’t always know what record was in what form. I finally scanned all of my paper records and filed them electronically. I love that I can easily take all of my records with me on my laptop. I now keep only original records in paper form, and scans of those are included in my electronic files. Whichever system you use, you need a logical organization system so you can find what you are looking for.

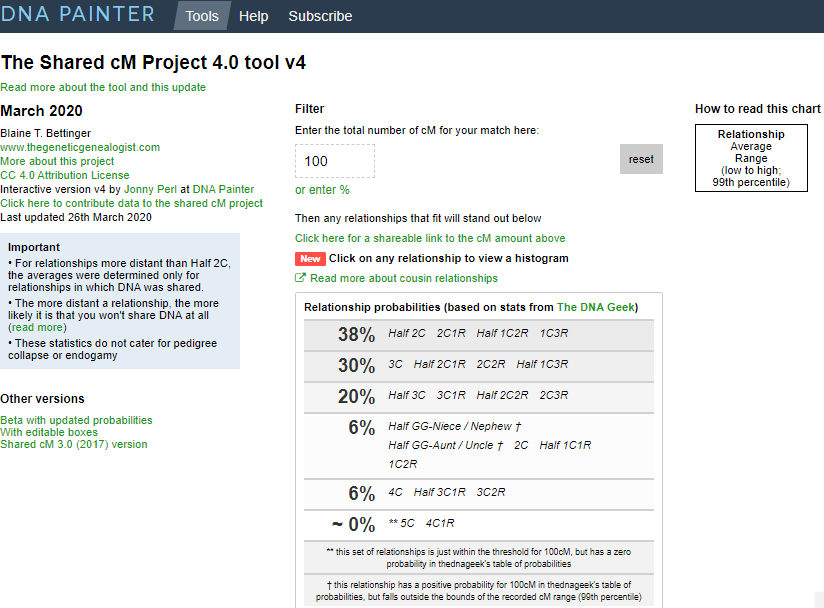

The DNA testing sites give you a range of possible relationships for each match, but which are the most likely? The Shared cM Project hosted at DNA Painter is a great tool that gives you relationship probabilities based on the amount of shared DNA.

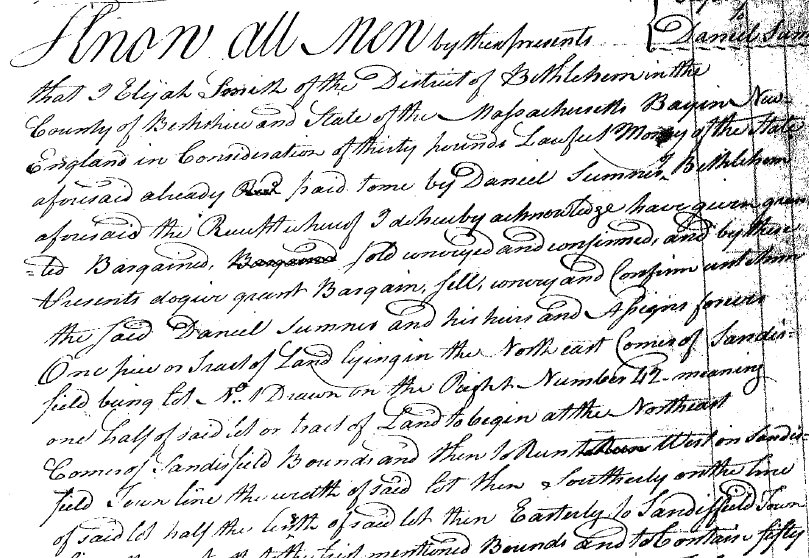

Land records, including grantor and grantee deeds and mortgages, can provide the name of an individual’s wife and other family members, as well as information on a prior place of residence. Individuals may have left many land records as they expanded their holdings or moved from place to place.

For times before detailed vital records were kept, probate records can be among the most valuable records providing direct evidence of family relationships. Probate records, which can include wills, petitions for administration, inventories and distribution of property, often list all living children, including daughters’ married names, as well as the children of deceased children. Be sure to search for probate records for both parents, as well as grandparents and (especially ummarried) aunts and uncles.

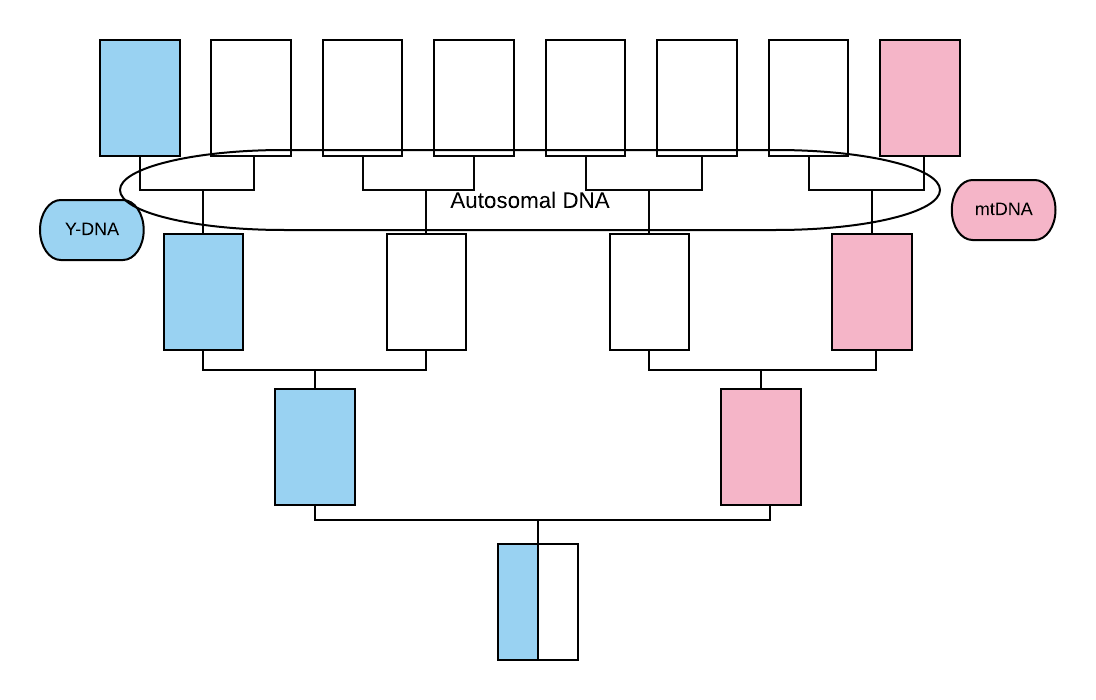

Autosomal DNA is the most commonly used DNA test for genealogy. It has the advantage of potentially providing information on all branches of your genetic family tree, however, its utility diminishes after a few generations. You have a >90% probability of sharing DNA with third cousins, with whom you share great-great-grandparents, but the probability of sharing DNA decreases rapidly to less than about 10% between sixth cousins. Y-DNA and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), by contrast, only provide information on the direct paternal and maternal lines, respectively, but as there is no recombination, these types of DNA can provide information for many more generations.

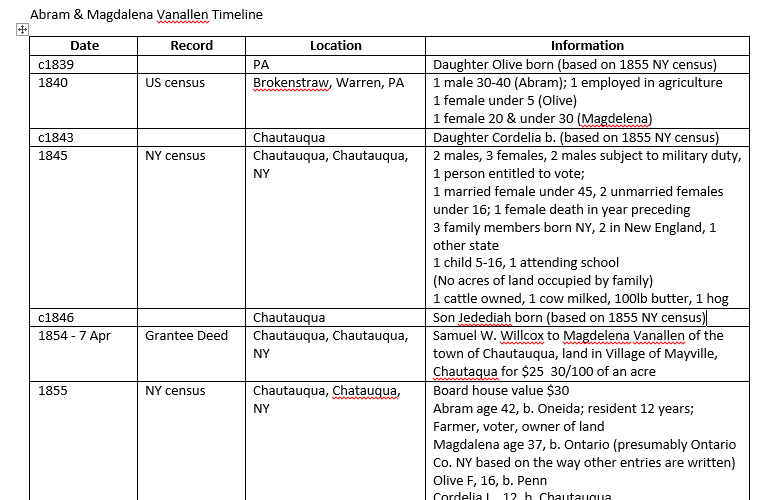

Creating a timeline for an ancestor or family can be a great tool to find gaps and inconsistencies in your information. You can use any format you prefer; I usually create a table within my research summary document and customize the columns and information depending on the research question. The timeline can help you visualize where information may be missing, or where entries may be in conflict.

Once your research question is defined, the next step is a research plan. What records have you already looked at? What records are likely to contain the information you are seeking? Where are those records held? List all the possibilities you can think of, prioritize based on the highest probability of success and then execute the plan.

Have you just taken a DNA test and don’t know what to do next? Roberta Estes has a great article on her blog DNAeXplained that explains how to get started.

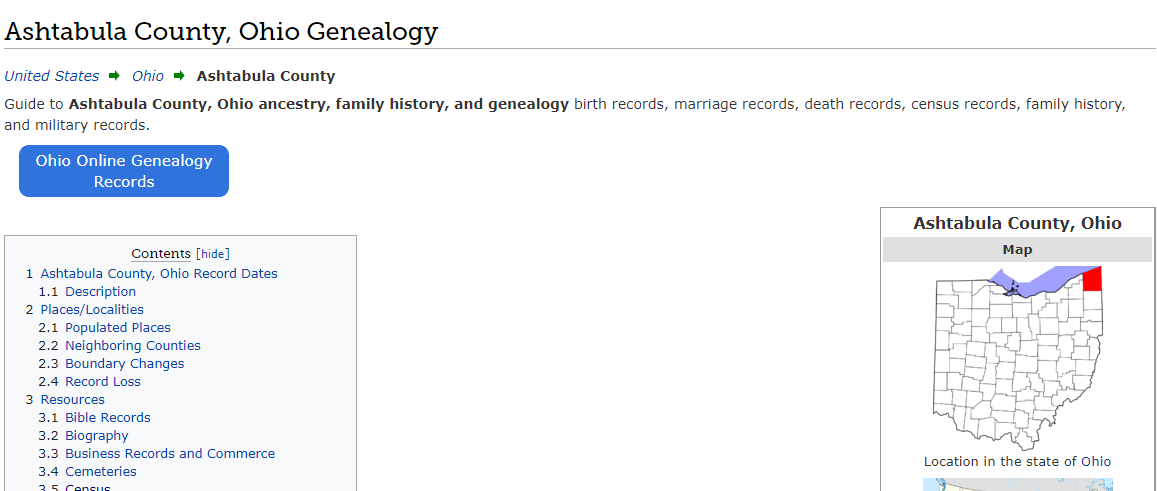

When you begin researching in a new location you need to learn about the locale’s geography and history, as well as what relevant records exist and where they are located. It can be useful to create your own locality guide that includes the information relevant to your personal research, and a great place to start is the FamilySearch Wiki – the page for each locale is a treasure trove of helpful information!

Ethnicity estimates are a fun introduction to genetic genealogy, but they are really only accurate to the continent level. The results are highly dependent upon the reference population each testing vendor uses, so they can vary significantly. So don’t worry if your ethnicity estimate is not what you expected!

Do you know what your research question is? Without a clearly defined question, research lacks focus and it is easy to go down rabbit holes in random searches. The research question is the first step in defining your research plan. It should be sufficiently narrow and well-defined that there is a clear answer, such as “Who is the father of John Doe?”, as opposed to “I want to learn everything I can about the Doe family.”